by Anuradhi Jayasinghe

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the issue of the maximum utilisation of scarce resources to the forefront – particularly, the issue of land use. The Sri Lankan mindset, influenced by cultural sentiments on possessing house ownership, has been traditionally driven by the need to own a plot of land and then build a house on it. This process is perceived by most Sri Lankans as an achievement regardless of the hardships and costs throughout the process. However, because of land scarcity, the rising prices of available lands and the costs of building a house, people in Colombo have moved onto other options.

For instance, they tend to buy already-built houses but not those built in separate plots of land – such as condominiums and apartments. Some have moved away from Colombo in search of plots of land which are affordable to build their own houses. But this second option has created yet another challenge – traffic congestion. The pandemic has highlighted the benefits of living that aligns with culturally ‘sentimental’ mindset of having separate houses in one’s own plot of land. Millennial lifestyles in Colombo – lives lead in apartments – have sometimes failed to respond to the pandemic. Complying with pandemic guidelines (e.g. maintaining social distancing) and maintaining mental, material, and social wellbeing simultaneously is quite impossible when living inside highly concentrated and high rise buildings.

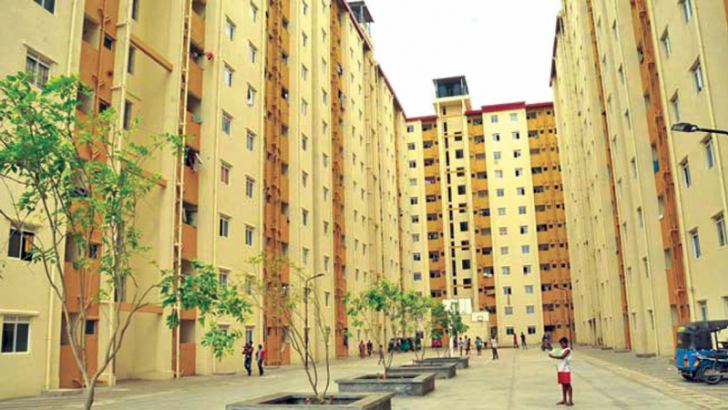

Life in an apartment in Colombo is not the same for everyone because living in an apartment (either in a formal and luxurious setting or informal highly concentrated high-rise apartments) has not been the first choice for everyone. This is definitely the case for residents of underserved areas who have been relocated and resettled involuntarily in these high-rises. During the last lockdown, the residents of the Siyapath Sevana Housing Scheme in Dematagoda launched protests claiming that the Rs.5000/- allowance by the government was not enough. This could be mainly due to the loss of the livelihoods of these residents who have previously lived in the Colombo 7 area. Still, these residents are struggling with this dilemma while being tagged as low-income families. This is another example of failed housing development programs in Sri Lanka although this re-location programme has been regarded as one of the most effective approaches next to on-site upgrading of under-served settlements.

The re-settlement program seems to have only considered just shifting the residents from one place to another but not the livelihoods that they have engaged with. Moreover, residents in these highly concentrated high-rise flats have an equal chance of facing disease outbreaks as they were when they were living in their previous houses, within small separate plots of land with shared sanitary facilities. As opposed to living horizontally, these residents are now living vertically with the same congestion. It is true that now they have separate sanitary facilities yet, the shared spaces for instance when using elevators facilitate the easy spread of diseases like COVID-19. This is different from other luxurious apartment systems in Colombo where they have enough facilities, especially with regard to the space given per family. For instance, very few people use one elevator at a time due to the higher availability of elevators in a luxury condominium. Moreover, residents living in very formal and luxurious apartments are not experiencing the same challenge in collecting food during the lockdown as for the residents in high-rises such as the Siyapath Sevana scheme. The majority of the Siyapath Sevana residents are daily wage earners, and Sri Lanka still lacks an effective ration distribution program during lockdowns to feed those who need it the most.

Above all, the high rising buildings for low-income residents are not equipped with facilities to promote the mental health of young and adults. If they were supported with such facilities for the residents to enjoy – for instance, libraries, indoor playgrounds, and gyms – they could live considering themselves as within in a bio-bubble during the lockdown.

The resettlement approaches of underserved communities under the Colombo City beautification project has tried to fit all income categories into the same design – the vertical living design. Nevertheless, the components or the facilities and the wellbeing aspirations of the design differs between poor and rich. The pandemic has proved that relocating low-income communities into vertical designs is a failed approach not only for the wellbeing of the residents but also to adapt to future pandemic scenarios. Thus, urban planning must be inclusive of disaster-risk-reduction planning and be a response to secure equal wellbeing aspirations by planning equitable cities. According to Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), such measures includes continuous assessment of the needs of the dwellers and identifying the resources for planning and implementing responses together with preparing for a resurgence.

Life in a city concentrated with people and activities is vulnerable to various stresses, both man-made and natural. As such, urban city planning is facing another challenge but has not yet been recognised – climate change risks. Urban development and climate change policies in Sri Lanka are planned and implemented in isolation, making cities more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Agriculture, water resources and coastal zones are the most popular among climate change discourses in Sri Lanka.

However, changes in the microclimate are no exception to risk with the current speed of climate change, especially the hot and humid climate found within the high-rise buildings with compromised wind movements in Colombo city. Increasing temperatures will exaggerate the ill conditions for wellbeing within the highly concentrated high-rise buildings. In addition, residents cannot afford air conditioners and increasing electricity bills to adapt to the increased temperature. Initiatives such as the installation of solar panels to ease the electricity burden of these residents is also absent. Guidelines proposed for the COVID-19 pandemic includes living in a place with an ample amount of sunlight and good ventilation. Most constructions in the Colombo district have altered wind movements, and the residents in concentrated high-rise buildings are the victims of the adverse consequences of such constructions.

This is just one example of how wealth inequality fuels the flow of resources among urban residents and dictates their level of adaptability to unprecedented risks. How can we build cities while accommodating for both pandemics and climate change risks? The planning and development of equitable cities in the first place is the very solution for any unprecedented risks, including both health and climate change risks. Treating people differently by allocating resources based on their income and their origins should not be the basis for urban resettlement programs, because even the COVID-19 pandemic has proved that equitability in city planning is sustainable, safe, and in the interest of public health.

__________________________________________________________________________Blog writers raise issues of contemporary relevance and contribute to a vibrant discussion on human rights and related issues. They express their personal views and not necessarily those of the LST, its Board and its members.Posted 13th September 2021 by Law and Society TrustLabels: city planningclimate changeDevelopmentRights based DevelopmentSri Lankaurban planning